This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

It is an easy mistake to make to consider the Nayabaru to be strictly hierarchical and assorted into tiers. Rather, their social structure might be described as “anarcho-totalitarian” - it grants very little leeway while in a framework of almost zero absolute hierarchy.

Respect

An important thing to understand amongst Nayabaru is that there are several ways to respect a person.

Title Respect

Most often, respect is given based on title and profession (these are often more or less identical, in that a title inherently represents a set of overlapping professions).

This respect is given to all Nayabaru, to the degree that they are a good representation of their title and profession, inasmuch as the Nayabaru in question can judge. For most Nayabaru, this means that they deal with each other with a base level of respect, since they cannot judge each other in the respective other profession. For members within a profession, this causes an (almost) meritocratic hierarchy.

It's important to understand that Title Respect is given wholly independent of personality - unless personality is an important aspect of the profession/title. It's no less real. A Nayabaru cannot turn off the Title Respect they feel, even to someone whose personality they find unseemly.

Nayabaru without Titles of course cannot get any Title Respect. This is bewildering amongst adult Nayabaru, and its strangeness can cause instinctive animosities.

Title Respect is easy to give between strangers.

Experience Respect

The second most frequent respect is one based on age and experience. This respect increases linearly relative to how long someone has been in a profession - for the vast majority of Nayabaru, this is identical with their age, minus a small offset. A larger difference may accrue in the case of someone who changed professions, although this is a very rare occurrence amongst Nayabaru, usually signifying a lost title.

This is a mostly abstract kind of respect. Someone outside the Nayabaru's profession will still not heed them any more about something not covered by their profession, but they will try harder not to be in the Nayabaru's way, and divert more resources to them if they are ill, in need of food, or water.

Nayabaru without Titles can get Experience Respect, although this is difficult, and only works amongst the community they reside in. Strangers cannot impart Experience Respect on the Titleless - but they can impart it on strangers that have held a Title for their entire lives. This is discernible through the Nayabaru tattoo system.

Social Respect

This is respect given on the level of how demonstrably honest and agreeable a Nayabaru is.

It is the respect that shapes young Nayabaru most of all (who can benefit neither of Title Respect nor Experience Respect). In these young Nayabaru, it decides what professions are open to them. Only the most respectable are considered as future Lashala.

This is not a hierarchical respect - it is a manifestation of communal protectiveness. The Nayabaru have niches for those low on Social Respect (as long as they do not fall into the negative, as criminals such as murderers and thieves would be) that they consider just as important for the community as the Lashala. Nonetheless, you want your Lashala to have a strong empathy and intense levels of honesty, whereas some professions have much less of a need of this trait.

In adult Nayabaru, Social Respect has very little bearing, although it can be cause for increased snits and disagreements based on a 'sense of nagging distrust' in those at the very bottom of the Social Respect gauge. Given these are all quite strictly regulated by the Lashala, this isn't much of a problem in practise, however.

By definition, Social Respect cannot be given amongst strangers - a reputation needs to be built, and the way Social Respect works on Nayabaru is that it only exists on a personal basis. A traveller thus will grant none of the strangers he meets any Social Respect - though this usually does not matter.

This respect is one of the most important assets of Titleless Nayabaru - the one they can bank on in the early years after choosing a profession or switching to a different one.

Friendship

Often discounted by Nayabaru if asked about this formally, and indeed a very weak bond, friendship does exist between Nayabaru. They are very social creatures and of course they enjoy the company of some Nayabaru over the company of other Nayabaru, independent of any respect they may have earned.

Friendship is the lubricant for specialisation where merit cannot distinguish the involved Nayabaru. Two Nayabaru Hesha that are friendly with each other and equally capable at interrogation and patrolling may split up the tasks amongst each other, so one becomes better at patrolling, and the other at interrogating, until merit can be used to justify the choice post-hoc.

Friendship is the first thing to be thrown under the bus when a problem arises, however. A Nayabaru will not help a friend that has gotten wrapped up in a dispute. It simply wouldn't occur to them.

Hierarchies

Lashala

One of the strangest positions amongst the Nayabaru are the Lashala. To someone who does not know Nayabaru society, they may seem to hold all the power.

Indeed, they are central to any Nayabaru community - but they do not lead anyone in it any more than any others in the community do.

Their job is to assess the correct profession for a young Nayabaru, to monitor the members of the community throughout their life, and to thus know enough about each Nayabaru to be able to make decisions if there is a professional dispute.

They decide the structure of a Nayabaru community as they assign the professions - however, they work on a generational basis. If someone comes to them requesting more Hesha, they will raise more Hesha, but it will take for them to become adults before this bears any fruit.

Reassigning professions is not typically done - definitely not for reasons of need of someone in a particular profession, and only very rarely on request of a Nayabaru who feels misfiled and wants a second chance in another profession (which is necessarily just a shortcut on falling from grace in their previous profession - the tattoo scars aren't optional). If there is truly urgent need for someone in a profession (e.g. the only Seklushi in town unexpectedly came to death), neighbouring communities will be asked for help until the next generation can fill in.

Note that Lashala typically do not bother to hold names - everyone refers to them simply as Lashal. If for some reason they were un-titled and survived the ordeal, they would be made to take on a four-letter name.

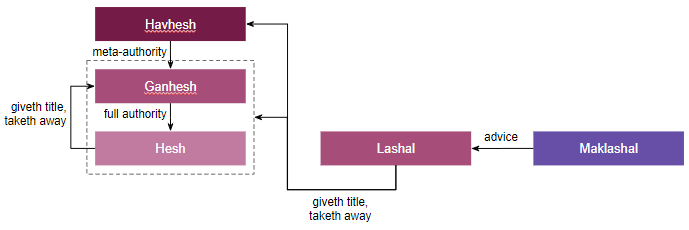

Gan-

The prefix “Gan-” to a title might be comparable approximately to the human habit of referring to respected people as “Master”, and describes actual hierarchy (although only within the profession).

“Gan-” is the prefix used within a group of Nayabaru with the same profession to refer to the one of highest respect. Amongst the profession itself, it is obsolete - the Nayabaru in the profession do not need to be told who their highest-ranking is. It is used outside of the profession, however, to direct enquiries to the most qualified. For example, a Nayabaru having a question about biology would be referred to the Ganseklushi of their community. (The Ganseklushi in turn might refer to a lower-ranking Nayabaru if they are busy, but they're considered a first contact.)

The different professions group differently, based on how many of them exist in a given community.

Some have several groups within a community, and in consequence several Gana. In larger towns, Hesha fall into this category - you might run into two or three Ganhesha there.

Some have one group within a community. In most places, Seklushia have only one group. Sometimes that group is as small as two - one Ganseklushi and one Seklushi, latter perhaps an apprentice.

Some are necessarily solitary within a community, and only group between neighbouring communities. Presently, this only concerns the Lashala, befitting their strange but important role in Nayabaru culture. The Ganlashal is one that decides on who may be a Lashal when a community's Lashal dies without having decided on and/or educated an heir. The Ganlashal is the most respected Lashal in all immediately neighbouring communities. (This means that two neighbouring communities may, indeed, have different Ganlashala! This is totally normal.)

Gan- titles are consensus work. If there is dispute, no one is Gan. If a Gan is necessary for the group to function, the community's Lashal may arbitrate until a Gan is found. Uncooperative Nayabaru will be excommunicated with no hesitation.

One can become Gan through good work alone.

Hav-

Hava, on the other hand, are chosen positions, filled by the Lashala like any other profession. The prefix can be translated, roughly, as “ultimate”. The associated tattoo changes are complementary, so that at least in theory, a Nayabaru in the basic profession can be upgraded to a Hav if the need arises, but this is avoided if at all possible.

Hava resolve disagreements between Gana, and coordinate them for the whole community, or between communities where no more than one group of the profession exists in a single community, but they may not do what humans would call “micro-managing”, and they may not second-guess the actions of the Gana where they do not interfere with the stated meta-goal.

How many Hava there are for a profession overall depends on the need for coordination, which is usually low. The fewest professions even have them. A few examples:

- The Karesejat is Havhesh - a position that was considered important for the high time of the kavkem ↔ Nayabaru war, but has since effectively been absorbed into the title Karesejat and thus not usually used as a term any more.

- The largest communities in Vatenas each have a Havdarhal and Havbaskaat.

- Marmoa do not have Hava, although they may temporarily agree on a kind of Havmarmo when the need of a great artistic or architectural project arises that pools several Marmoa and their Gana together.

- Seklushia do not have Hava.

- Yeresoa do not have Hava.

Mak-

Maka might be tentatively translated as “penultimate”. They are similar to the concept of Hava, with an important distinction: They cannot decide anything. They resolve disputes between Gana, possibly even between Hava, but their resolution is one that must be assessed by the parties in the dispute and accepted or rejected individually. In addition, their knowledge of the profession is strictly theoretical - if they were to practise the profession, they would not be chosen as Maka.

Maka are rarely permanent. They might be particularly booksmart Nayabaru that are chosen by the Lashal on the spur of a moment to resolve a matter. Nonetheless, a handful of permanent Maka exist.

Of these, the most notable are that the Karesejat is Maklashal and Makdarhal, both:

She 'judges over' any Lashala in dispute that call upon her for dispute resolution. She cannot enforce her decision. She cannot muscle in on a dispute that she considers her presence useful in, either. She must wait for the Lashala to approach her.

Makdarhal is of course far less spectacular. It corresponds to what humans would diagnose as “well, d'oh, she's the most intelligent person on the planet, and she understands physics better than anyone”.

Karesejat

The title Karesejat is a war-time creation and it has persisted since then. It would likely disappear once the kavkema are extinct (not that this is likely to ever happen). The Karesejat is many things, but most notably:

- Havhesh - she is the supreme commander of all military forces, no questions asked.

- Maklashal - she advises the Lashala if there are disputes amongst them.

- Makdarhal - she advises the Darhala if there are disputes amongst them.

- automatically grants a high Social Respect even amongst strangers.

The current Karesejat, Terenyira, in particular is endowed with an extremely high Social Respect due to how well-known she is as an individual. She also enjoys near-infinite Experience Respect due to her current nature as a de-facto immortal being.

Resulting Structure

Interaction Rules

The Nayabaru social structure is quite instinctive for them, although trying to chart it quickly becomes unwieldy. It follows a few basic de-facto rules that cause some rather complex social structures to arise:

- “I may not obstruct anyone in their profession.”

and the complement:

“Nayabaru outside of my profession cannot tell me how to do my profession.” (often supplemented with the non-instinctual, cultural “I will not be offended by Nayabaru outside of my profession saying necessarily stupid things about my profession”)

- “It is important that I act in accordance with my profession as well as I can.”

and the complement:

“Nayabaru within my profession should constantly be assessed for their merit; if my merit exceeds theirs, I have the responsibility to teach them and take care of them; if their merit exceeds mine, I have the responsibility to do as they say.”

- “It is important that I am useful for the community.”

and the complement:

“If any Nayabaru appears to me to not be useful, I must confront them. If they do not convince me of their merit, I must report them.”

- “If I am asked for advice on any matter, I must give it, without bias as to whether it will be heeded.”

and the complement:

“If I need advice, I may ask anyone.”

(“It is not generally important what I do outside of my profession,” is something that follows logically but is worth pointing out explicitly.)

On top of those instinctive rules are the tattoo-based rules:

- “Nayabaru with tattoo scars are defective to the degree they are scarred and should not be trusted with anything relating to the scarred profession. No one can override this statement.”

- “Nayabaru tattooed with shun-marks (or with tattoo scars of shun marks) from your region are to be driven out of your community by force. Nayabaru tattooed with shun-marks (or with tattoo scars of shun marks) from other communities are probably dangerous and should be avoided, arrested or exiled, unless your superiors say otherwise.”

Shunning is the worst form of punishment imaginable to the sociable Nayabaru. Solitude is an unbearable thought to them, and community with community-breakers is only marginally better (though preferable to solitude).

Dispute resolution

Nayabaru have strict rules defining what a dispute is and how it ought to be escalated.

Grumbling, whining, and complaining about circumstances are never a dispute. These will net the Nayabaru in question some negative Social Respect, but that needn't be a problem, given that it's low on the list of Respects to give.

Non-profession related insults are also not a dispute. Again, this will strip you of Social Respect. This usually means that such spats rapidly come to an end, as few are willing to respond in kind.

Profession-related insults, on the other hand, may be a dispute. It depends on whether they are simply rank-based - i.e. whether you are being shuffled down the pecking order - or if they are basic - i.e. you are challenged as to whether you befit the profession at all. Latter are a dispute. (It doesn't matter if these are from someone in your profession or outside of it. Any sort of verbal challenging of your basic merit in your profession is a dispute.) These are considered Title Disputes.

Professional disagreements are also a dispute, although these are often resolved before their 'dispute' nature becomes truly manifest. These are also considered Title Disputes (although in the early stages are rarely explicitly referred to as such).

Criminal activity is also a dispute - thievery, murder, vandalism. These are considered Acute Disputes.

Title Disputes

Title Disputes are escalated in the following manner:

- The parties of the disagreement speak with each other openly about the dispute. If they cannot come to a conclusion:

- The nearest Nayabaru of the same profession as the attacked's profession (which in some cases may be distinct from the attacker's profession) is asked for advice. If the attacked Nayabaru is considered in the right at this point or any further point, punishment befalls the attacker. If there is no such Nayabaru, they have no advice, the attacker is considered in the right, or the advice is not mutually acceptable to the disputing parties:

- The highest-merit Nayabaru of the attacked's profession that both Nayabaru agree on (usually the respective Gan) is asked to decide. If such a Nayabaru does not exist or they cannot decide:

- The Lashal of the attacked's community is asked to decide. If such a Nayabaru does not exist or they cannot decide:

- The Lashal of the attacker's community is asked to decide. If such a Nayabaru does not exist or they cannot decide:

- The Ganlashal of the attacked's community-region is asked to decide. If such a Nayabaru does not exist or they cannot decide:

- The Ganlashal of the attacker's community is asked to decide. If such a Nayabaru does not exist or they cannot decide:

- The Maklashal may optionally be asked for advice. If such a Nayabaru does not exist, they have no advice, or the advice is not mutually acceptable to the disputing parties:

- The disputing parties are both stripped of their titles, tattoos and exiled from their respective communities.

It is generally considered highly shameful to have to go to the Lashala.

Acute Disputes

Acute Disputes are so named as they require immediate action. A matter considered an Acute Dispute will result in any involved parties being detained as soon as possible, with as much force applied as necessary. The Lashal of the community will be alerted and (1) investigate to what degree an actual crime occurred (occasionally, such things are just a misunderstanding) by speaking with witnesses and/or inspecting records, (2) choose how to deal with the matter.

Punishment

There are several options available to Lashala:

- Reparations

The most frequent punishment for minor infractions and disputes - the offending Nayabaru will be asked to make reparations, going either to affected victim(s) (rarely) or to their community (often, unless it makes no sense). - Incarceration

Rarely used - the Nayabaru is kept in a prison-like environment for a while. They only have contact with their Hesh during this time. Such times are usually kept short, as they are considered barbaric. - Torture

Even more rarely used - only of interest if the captive Nayabaru could give information of value to the interrogators (e.g. location of a kidnap victim, if such a thing were to ever happen - or where his fellow thievers took the loot). Usually, the threat of exile or incarceration is enough, but for those already exiled neither of those tend to be good deterrents. Exiled Nayabaru may leave torture-encounters with quite a few fingers fewer than they went in, even if they are quick to yield. - Title-Stripping

The removal of the Nayabaru's title and the associated tattoos. The Nayabaru must sacrifice one glyph from their name, but may return to the community, taking on a different profession. This is a very public and highly humiliating ritual. - Exile

The removal of the Nayabaru's title and the associated tattoos. The Nayabaru loses their name and their right to a name (formally - informally, it is often “kept” but scrambled by the affected Nayabaru). The Nayabaru gets a neck-tattoo, marking them as an exiled Nayabaru. This, too, is a very public and highly humiliating ritual.